Originally published under the name: La inteligencia artificial y la fe parte II ¿Llegó el transhumanismo a la iglesia?

written and translated by Adriana Celis

Can a robot be a suitable helper for pastors? From this basic but profound question arise other queries, such as: Do robot deacons exist? What is transhumanism? Are we all transhumanists? What is the theological opinion on this? And what is the technological opinion on this?

In today’s society, where the culture of instant gratification prevails, it is clear that some pastors are often apathetic and cold, while others, on the contrary, are humble and upright—true servants of the Almighty God. However, despite this reality, we cannot deny that they are still human beings and cannot fully meet the current needs of their communities. The large-scale migration happening worldwide, especially in the United States, along with other problems, has led to an overload of work for pastors. This has changed how they manage time, handle stress, and prepare sermons. For this reason, some pastors have found help beyond the earthly realm, and yes, this help often does not come from divinity but from artificial intelligence (AI).

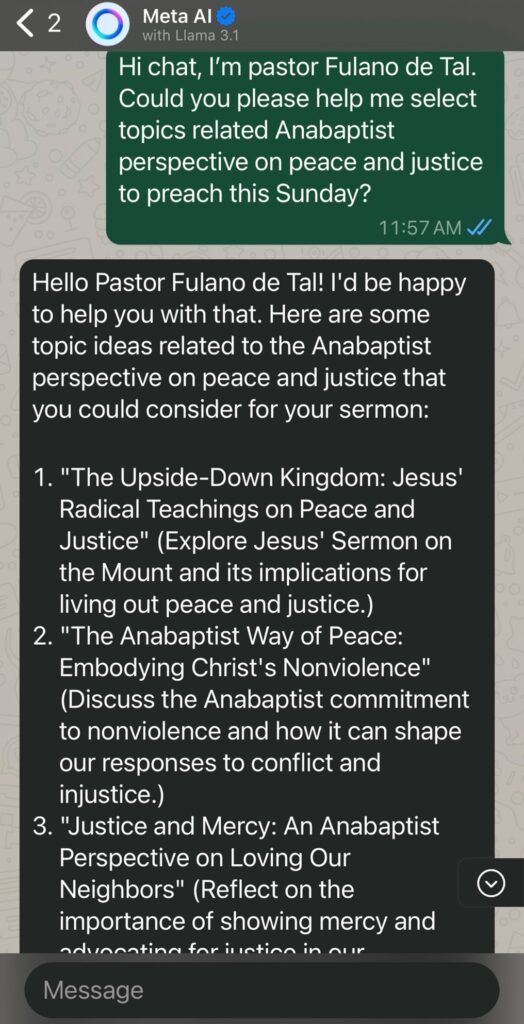

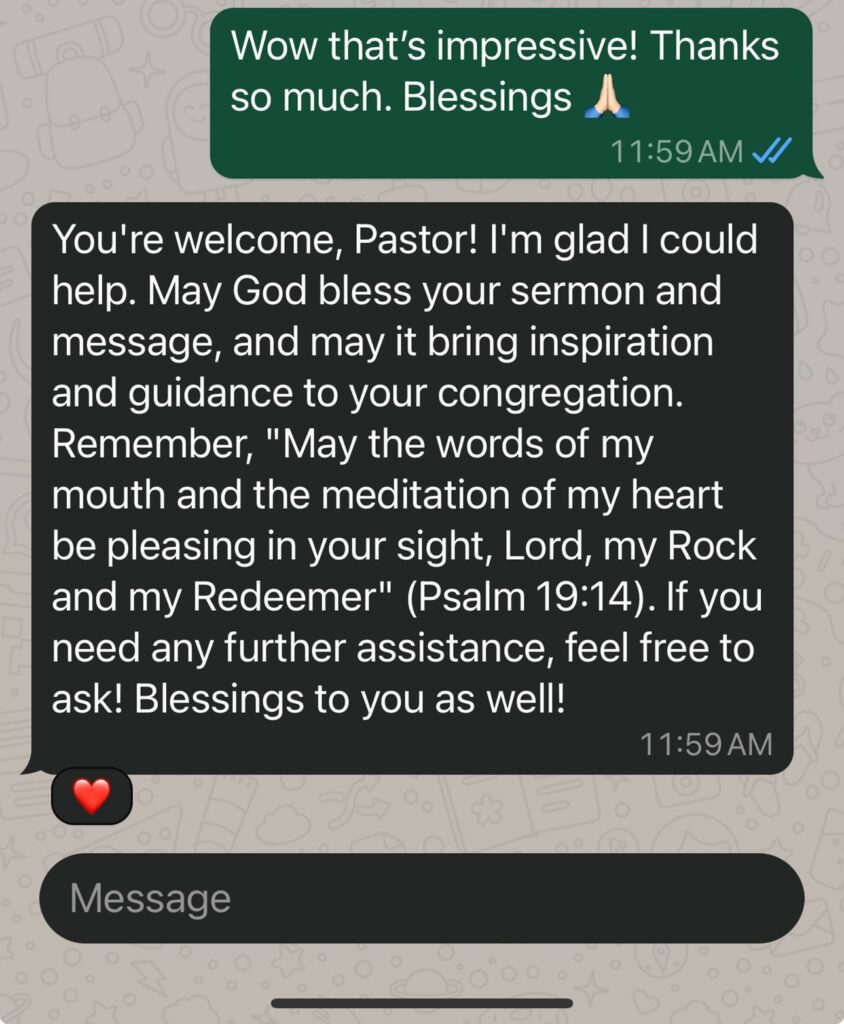

According to Relevant Magazine, many pastors in North America are already consulting AI for their Sunday sermons. Modern deacons could be chatbots like ChatGPT or Meta AI’s chatbot service, which has recently been introduced on platforms like WhatsApp and Instagram. The MenoTicias team, in a proactive manner, decided to ask Meta’s AI a question, as shown below: “Hello, can you help me write the Sunday sermon?” We witnessed how the AI offered many options; it can even sign off affectionately, as shown below.

But not everything related to AI is wonderful. AI raises other ethical and moral issues, particularly when spiritual practice is based on the solutions provided by AI and not the Word of God.

It is worth noting that these solutions are based on the data provided to the AI—data related to the age of congregants, their gender, sexual orientation, intellectual level, and, yes, their beliefs. These algorithms have entered the church in the form of AI or chatbots and have been a source of help to pastors. We cannot deny this. But how far can their reach extend? And how reliable can they be?

In light of these doubts, we decided to compare several opinions, the first from a theological perspective and the second from an innovative one.

Theological Perspective

We spoke with Fernando Pérez Ventura, a Mexican living in Morelos, Mexico. He is a professional in International Relations from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), with a Master’s degree in Biblical Sciences from the Theological Community of Mexico and in Logotherapy from the DAU Institute in Peru, in collaboration with the University of Vienna, Austria.

Drawing from his expertise working with theological institutions like CITA (the Community of Anabaptist Theological Institutions), Fernando, commented on AI:

“It is a technological tool, and depending on its use, it will be appropriated in human societies. This is where the biblical-theological work on ethics comes in. The fascination with a discovery or technological tool like this can reduce our human, social, political, cultural, and religious perceptions. No technological tool, political party, or existing ideology can reduce the culture of the Kingdom of God among us. I believe we have neglected our theological reflection.

AI will not remain solely in the realm of robotics; it will delve into the phenomenon called transhumanism – enhancing the human with AI – which has sparked countless philosophical and theological discussions worldwide. In Latin America, the Christian church is still in its infancy, and yes, it is essential to enter the contextual discussion of this phenomenon.”

Innovative Perspective

To examine this issue from an innovative perspective. we spoke with Leidy Johanna Celis P., a Colombian lawyer from the Autonomous University of Bucaramanga specializing in Intellectual Property at the Externado University of Colombia and courses in Patents and Copyright at Harvard Law School. She explained what transhumanism is and how, at some point, we have all been transhumanists.

“First of all, it is necessary to highlight that transhumanism is an intellectual movement that ‘advocates overcoming the current limitations of human beings, both in their physical and mental capacities, through the development of science and the application of technological advances.’[1] This movement has its challenges and benefits, one of which is improving the human condition. So, we could think they are fulfilling the biblical mandate to care for one’s neighbor. And the truth is that all of us, at some point, have been transhumanists since we are using technological elements that help us improve life. On the other hand, humans were born with the intention of being eternal, but this plan was frustrated when sin entered human life. For this reason, it is not surprising that such a movement seeks immortality and the improvement of humans on Earth through the use of technological devices.”

As Johanna Celis explains, at some point in life, transhumanism has been part of our daily lives since “today, it is common to incorporate technological devices into the human body, such as brain implants, bionic prosthetics, microchips to make purchases, contact lenses to improve daytime and nighttime vision, as well as modify and implant memories to treat diseases.”

In conclusion, there may be many transhumanists in our faith communities who, without realizing it, have lived among us.

[1] Celis Pinzón, L.J. (2024). Patentability exceptions: a focus on the CRISPR-Cas9 technology case. Does it constitute a violation of public order, morality, and good customs? Revista La Propiedad Inmaterial. 37 (March 2024), 65–101. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18601/16571959.n37.03.